|

|

||

It is a fraud. It's disgusting to the heritage of the tribal people. And it's just … insulting to my parents.

The best way that I could think of summing up my sister is that she created a fantasy. She lived in a fantasy, and she died in a fantasy. The thing about ‘Dumbo,' is that's why I think my days with Disney are done, I realized that I was Dumbo, that I was working in this horrible big circus and I needed to escape. That movie is quite autobiographical at a certain level. Sir John Major is not alone in his concerns that the latest season of ‘The Crown' will present an inaccurate and hurtful account of history. Given some of the wounding suggestions apparently contained in the new series — that King Charles plotted for his mother to abdicate, for example, or once suggested his mother's parenting was so deficient that she might have deserved a jail sentence — this is both cruelly unjust to the individuals and damaging to the institution they represent. No one is a greater believer in artistic freedom than I, but this cannot go unchallenged. These days, there is a cynicism and overall pessimism in the air, which, considering that the world is offering much more to everybody than it ever did, is surprising. For example, in Hollywood, the ending can never be too upbeat: the ending has to be somewhat depressed or compromised; otherwise, you're accused of being sentimental or saccharine, or you are not taken seriously. That's very much in the air. There are no good endings anymore...

Where is the joy of life? We need that. I want movies that have optimism. Movies have to, in some ways, pay homage to cynicism, and I am always not happy with that. I remember in seventh grade after reading ‘Dracula,' having feelings about it and going, ‘Something more is going on here.' Then looking up Bram Stoker, seeing he's married with kids and being disappointed. So there's something about a little bit of wish fulfillment where it's like, I knew it. I knew there was something queer about this story. That's incredibly satisfying. From Breathless on, Godard redefined the very idea of what a movie was and where it could go. No one was as daring as Godard. You'd watch ‘Vivre Sa Vie' or ‘Contempt' or Made in USA and you had the impression that he was actually taking apart his own movie and rebuilding it before your eyes. You never knew what to expect from moment to moment, even from frame to frame – that's how deep his engagement with cinema went. In the ‘70s you had movies where characters weren't necessarily the hero, they were fucked up, but they were interesting characters and you sat down and you followed them whether it be Travis Bickle or Charlie Rane in Rolling Thunder …they weren't the heroes…and they could die meaninglessly at the end, that was actually considered a commercial ending back in the 70s because it just shows how you can't win, everything's fucked, you just can't win in America. Everything was cynical, then all of a sudden in the ‘80s all that was washed away and the most important thing about a character was that they were likeable…Every character had to be likeable and the audience had to like everybody.

|

||

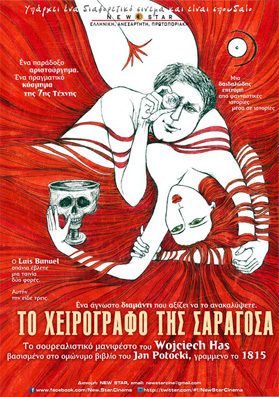

Note: Magical-Realist Films from Latin America

|

||

For six months, they took all my actions and turned them into computer data. Everything was copied down, and the copyright was owned by them. The martial arts that I practiced for a lifetime became copyrighted by the Americans. [Shortly after Binoche won her prize at Cannes in 2010, she was rudely disparaged in the press by Gérard Depardieu, who asked: “Please can you explain to me what the mystery of Juliette Binoche is meant to be?” before concluding that “she has nothing – absolutely nothing”.] I am hitting the same kind of themes. Here's a man who feels needs to be punished, who's waiting for that punishment to come, and then instead hopes that punishment will be some sort of redemption. It's a disease you can't take away; you can work with the symptoms, though. I just have to get used to that I shake and not be shameful in front of people. And then continue, because what else should I do? I see Gummo as a true science fiction film in the way it shows a scary vision of the future: a loss of soul, a loss of spirituality. And yet you clearly see all that with very tender eyes. When the time came for a second Godfather, I thought it was an absurd idea; The Godfather was complete after The Godfather. I didn't want to do it again; I wanted to do something else. If you make films you don't know how to make, you learn a lot. If you make films you do know how to make, you make a lot of money, but you don't learn a lot. So I was more curious about going on into different forms. [Then]

they made me an offer I couldn't refuse... I feel like the New York independent cinema really shifted after 9/11 because all the casting people left. A lot of the production offices closed. The whole movie industry that was in New York left, but before that, it was very thriving, which I think in turn, made the '90s so much more interesting, because there were a lot of creatives coming out of New York. Oh, I definitely would not be making films in the way I make them had it not been for medical school. First of all, it's all about point of view. As a doctor, you're looking at the complete human being, down a microscope or on an X-ray or as part of a collective. Viscerally, intellectually, spiritually, anthropologically. And then, on a practical level, it's invaluable. I think people are making movies for the wrong reasons. It's like, ‘I want to write a movie to write a movie. I'm going to get it made.' And it's, ‘No, but why do you want to write this movie? What is your obsession with this that you can't put it down?' [Gus van Sant's] Mala Noche is a film I saw before I wrote The Living End and the way Gus frames his male Adonises is very similar. I think, to me, it's a by-product of that time. It was about the revolutionary gay gaze at men and this objectification of men in the way that women have always been. That whole world of men being seen as sex objects and being lit and shot in a certain way was a huge visual influence on me...

Gay and queer representation was so limited at the time and, really, almost non-existent. When it screened at Sundance, I remember people were just so outraged. Seeing it today, it seems almost naive and a little bit cute. But it wasn't viewed that way [then.] It seems clear that the alien [in Nope ] and its relationship to attempts to capture it via surveillance are an allegory for law enforcement and police brutality. The at times absurd challenges of simply proving that this 'predator' is terrorizing people of color feel eerily familiar with the way law enforcement has continually abused its power and taken advantage of the Black community with little to no repercussions in the United States. Once you 'see' Nope's Alien this way it's hard to see it as much else. Lars von Trier would say remember to keep it messy. That was the mantra on

The House That Jack Built. And what that really meant was the potential for failure is important. You become a professional and you want to do everything right. And you want to do everything that you have learned. But all of that doesn't really matter because what's important are the moments of truth. Those real moments that happen. And they often happen by mistake. Because we're always trying to find other ways of reaching our goals, I think Iranian directors are among the most inventive in the world. That permanent confrontation with obstacles makes them more inventive and more questioning of themselves, their habits and the world around them...

That's our DNA, that's Iranian culture. You always have to navigate between what can be said and how to say it. I always look back at the periods that I perceived as the hardest as being the ones with the most growth. It seems funny, but there was a period right before “Training Day” where I couldn't get a fucking job because I was the Gen-X poster boy and everyone thought they knew me. I was supposed to be washed out to sea with that fad. I remember I wanted to get an audition for “Saving Private Ryan” and I couldn't fucking get it. Everyone knew who I was and they didn't want me. I'm sure if you talk to Matt Dillon or DiCaprio — anybody who's had young success — they'll acknowledge that you hit these walls where people think they've figured you out and then they're done with you. You have to be willing to be humble enough to keep getting up to the plate. I think

[Peter Weir]

lost interest in movies. He really enjoyed that work when he didn't have actors giving him a hard time. Russell Crowe and Johnny Depp broke him. He's someone so rare these days, a popular artist. He makes mainstream movies that are artistic. To have the budget to do “The Truman Show” or “Master and Commander,” you need a Jim Carrey or Russell Crowe. I think Harrison Ford and Gerard Depardieu were his sort of actors. They were director-friendly and didn't see themselves as important. When you see a big-budget effects film from James Cameron, you always recognize that the story comes first, and the special effects are only there to help the story. Whereas with Marvel, it sometimes feels like the special effects are the stars, and the story frankly can be filler between the special effects. You're asking a guy who made ‘Goodfellas' what he thinks about Spider-Man, what do you think you're going to get? He's a very serious filmmaker, and he's a man who's of a certain age and stuck in his ways. You should not be surprised that's his response...

Guess what? For every old filmmaker who's like,

‘I don't get it,' there's a bunch of young filmmakers who are like, ‘I get it and I want to do it.' We don't have to ostracize the people that maybe don't get or aren't into the same movies we are. This sounds super uber-precious, but I think it's hard to do this kind of creative work in a modern secular society because it becomes all about your ego and yourself. And I am envious — this is the horrible part — I'm envious of medieval craftsmen who are doing the work for God. And that becomes a way to … you get to be creative to celebrate something else. And also, you're censoring yourself because it's not about like me, me, me, me, me, me. So you say, ‘Oh, I got to rein that back because that's not what this altar piece needs to be.' Any worldview where everything around them is full of meaning is exciting to me, because we live in such a tiresome, lame, commercial culture now. Monsters are symbols of mystery... they reflect our need to find meaning in our lives. I think human beings need, or are drawn, to externalise mystery. We like to be humbled by forces in nature and in our world that seem to be unexplained. [Given it's] probable we know we don't know everything, we still have so many questions. And sometimes those questions coalesce into the shape of monsters, benign and otherwise.

|

||

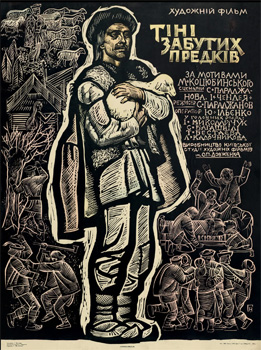

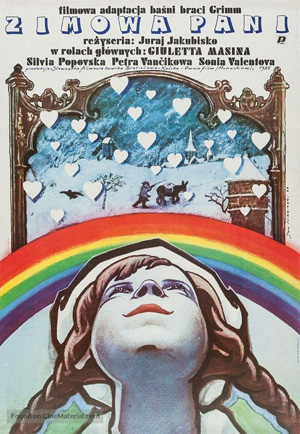

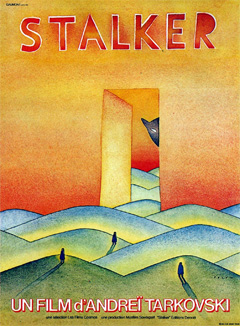

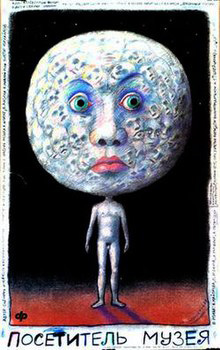

Note: Supernatural films from Eastern Europe

|

||

I try to be a witness to something. I try to preserve what I see. There's a sense of preservation in my films from the beginning: of landscapes, houses, characters. The act of filming is so precious. The photographer – myself – will be gone one day, but the photo is still there. I'm totally irritated by the notion of that you might need to go through more than one season of a TV show to start to be entertained by that fucking story. You know, like, I'm old-school that way, coming out of network television. Every episode needs to tell a story. And then each of those stories needs to build up to a season-wide story. And then that season's one story needs to fucking end. And then the next season, you can start a new one that builds off that. The whole idea of “I'm actually making a 20-hour movie?” Fuck you, you're in the TV business. You're in the entertainment business, and it's your job to be entertaining... One of the problems with recent superhero films is that no matter how good the set-up is, the climax always comes down to digital doubles shooting fireballs at each other. What I loved about your film [Everything Everywhere All at Once] is that the finale is an emotional battle. The ultimate resolution is not one person destroying another, it's a reconciliation. You come back to a really quiet moment after all the Sturm und Drang. At what point in the genesis did you know where this was heading? To boil down more than 2,000 years of Buddhist discourse – it is thought that all things exist only through our perception of said things. Therefore, they are without inherent meaning. They're empty. This is expressed in

[Everything Everywhere All at Once's] multiverses. When its characters gain the power to manifest all the potentialities of their lives, they quickly realise that when every phenomenon and concept you can think of are smooshed together, it all becomes a smorgasbord of meaningless nothingness – on top of a bagel. It loses inherent value. [Mr. Bean was a] self-centred, narcissistic anarchist [who was actually] a nine-year-old trapped in a man's body.

A lot of people didn't like the inevitable and justifiable feeling that things were going to go wrong. Terry Gilliam was erratic, a dreamer, someone who didn't live in the world of ‘logic and reason' – just as the Baron Munchausen himself didn't...

Though he was magical and brilliant and made images and stories that will live for a long, long time. It's hard to calculate whether they were worth the price of the hell that so many went through over the years to help him make them. Spielberg had already defied the expectation of a hostile alien invasion earlier with Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which expressed hope that such interspecies contact might bring out the best in humankind. The squat, murmuring, doe-eyed being in ET is much more of a device, serving to illuminate the loneliness and stress of a latchkey kid who hasn't settled into his new situation. Though the film never says how long Elliott's dad has been out of the house, it seems recent enough for everyone to feel unsettled by it. The alien brings Elliott closer to his siblings, as they work together to shelter it and figure out what it needs, but they're both trying to get back to their families. As Elliott helps ET go home, he learns to accept a newly reconstituted version of what home means to him, too. Coming out of an art school, I was trained to make a film that I believed in. I was trained to make the film that I thought was right... and not worry about people not understanding it... You have nothing to lose [making your first film]. You just do what you wanna do. Even with the second film, there's too much to lose. With "Chan Is Missing" being so successful, at least as an independent film, you kind of go, what if I don't get the reviews and don't get the support? So it's already starting to eat into you. There's a line in the movie [‘Benediction' ] where I thought, “This is completely you.” The older Siegfried Sassoon is asked by his son, “Why do you hate the modern world?” And Siegfried says, “Because it's younger than I am.” I forget which awards I've won. I have to look at my shelf to see what they are. I'm not being arrogant. It's the truth. You often know that the awards-givers are doing it more for themselves than for you. They need somebody to be a figurehead for the festival or whatever. It's a little bit transactional in a way. It's just not the reason I'm making movies. [So what is that reason?] To be an artist, to create, and connect with human beings. Cinema is not my life. I have three kids, four grandchildren. That's life. People tell me that I make films about reality. They're wrong. I make films about structures that I have thought up. Some people felt that ‘Top Gun' was a right-wing film to promote the Navy. And a lot of kids loved it. But I want the kids to know that that's not the way war is — that ‘Top Gun' was just an amusement park ride, a fun film with a PG-13 rating that was not supposed to be reality. That's why I didn't go on and make ‘Top Gun II' and III and IV and V. That would have been irresponsible. But let me say one thing about ecstatic truth. The simplest way to explain it is by looking at Michelangelo's Pietà, the statue. Jesus in the arms of Mary is a thirty-three-year-old man, tormented on a cross and taken down, but his mother is only seventeen. It's one of the most beautiful sculptures that was ever created. And my question now is did Michelangelo try to cheat us, did he try to give us fake news, defraud us, lie to us? The answer, of course, is no. He shows us a deeper truth of both figures. We have a word for that in Japanese. It's called ma. Emptiness. It's there intentionally. The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb. The point of RoboCop, of course, is it is a Christ story. It is about a guy that gets crucified after 50 minutes, then is resurrected in the next 50 minutes and then is like the super-cop of the world, but is also a Jesus figure as he walks over water at the end. It was [shot in] an abandoned steel factory in Pittsburgh. I put something just underneath the water so [Weller] could walk over the water and say this wonderful line… ‘I am not arresting you anymore.' Meaning, ‘I'm going to shoot you.' And that is of course the American Jesus. I have no choice but to make the films in Iran because I know these people better than I know people anywhere else. We were able to make this in peace. We tried to not make headlines with the film so they weren't sensitive about it. First you make the film, then you think about the issues that exist for it. There are too many cooks in the kitchen. So far the results are good, if you have a good chef, like Steven [Spielberg]. But the moment the director is not involved, [the cinematographer loses] control of the image.

My contribution

[on Ready Player One] was 40 percent. Apichatpong

Weerasethakul's previous films (Topical Malady, Uncle Boonmee, Syndromes and a Century) typically avoided Western nostrums — which appealed to the tastes of Western cynics who ironically praised the U.S.-trained filmmaker as if he were some Asian shaman. But his fondness for dense, Rousseauian tableaux indicates a different mindset. Memoria is the first Weerasethakul film in which the settings (traversing Colombian towns and jungles) evince Western influence. One thing I really remember about the process after

Brokeback Mountain came out was Heath Ledger never wanting to make a joke, even as, culturally, there were many jokes being made about the movie… His consummate devotion to how serious and important the relationship between those two characters showed me, I think, how devoted he was as an actor, and how devoted he was to the goals and story of the movie. The original Scream mocked the outdated tropes of the horror genre that lacked any innovation, taunting the audiences' expectations for recycled material and anticipating a world where everyone would do anything to be recognized by the public. "Compartment No 6" was very well received in Russia. They were amazed that a foreign film-maker could so sympathetically represent Russia and Russians. Because Russians keep getting told by paranoid nationalists about Russophobia and that all foreigners are a threat. Have you ever seen a film called the Mirror? I was hypnotised! I've seen it 20 times, It's the closest I've got to a religion – to me he is God. And if I didn't dedicate the film to Tarkovsky, then everyone would say I was stealing from him. If you are stealing, then dedicate. I have stolen so much from Tarkovsky over the years; in order not to get arrested, I had to dedicate the film

[Antichrist (2009)]

to him. I should have done it a long time ago.

|

||

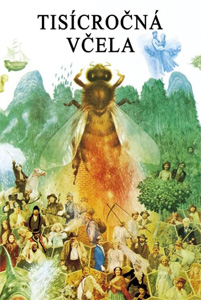

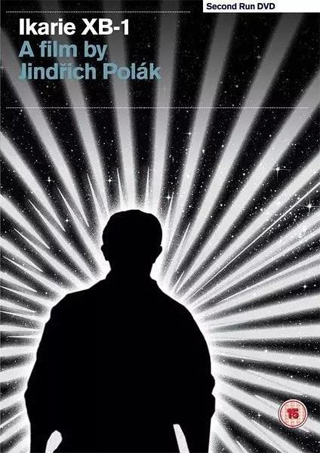

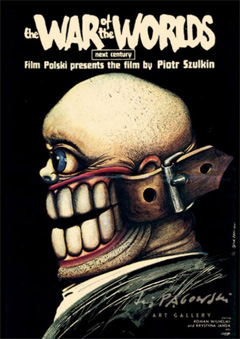

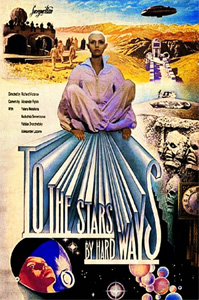

Note: Soviet sci-fi +

|

||

“After Yang” follows a long tradition of science-fiction narratives that fall under the category of “techno-Orientalism,” in which the future is often figured as Asian, and Asians are often figured as robots. The genre is historically understood as emerging from American anxieties about Japan's postwar economic boom, starting in the nineteen-seventies. Screenwriters write about people who are cooler than we are, stronger, better fighters… I write about people who are smarter than I am. I think it suits my writing style, which is romantic and idealistic. I'm very impressed by playwrights, whether it's Pinter or Mamet, who write characters who have a very difficult time communicating, but I don't have that club in my bag. Does being successful make it harder to stay funny? Is there more humor to be found in life when you're a lonely geek than there is when you live in a world of personal trainers and valet parking? I saw Citizen Kane on television for the first time, and I began to become aware of editing and camera positions. He was not afraid of being self-conscious with the camera and making self-referential remarks with the camera.

He did this with such conviction and with such brilliance that you began to realise ‘I see the camera moves'. And I started realising camera movement because he used that wide-angle lens a great deal, and if you use a wide-angle lens and you move quick enough, you see the walls speeding past you, you know? And this is what I think Welles bought to the cinema, to American cinema particularly. Because up until that time was the seamless film in away, the hidden camera, the camera that you couldn't tell was there. So, Welles was the one to really open up the pandora's box. I want movies to disturb me. But that's mainstream taste basically: People don't want to be disturbed. I don't think that's anything new…'Pink Flamingos' probably violates more values now than it did then. I remember one time there was a rainstorm when we were shooting ["The New World" ] in West Virginia, sheet lightning coming down and then forks, loud, loud, claps of thunder, deafening. And then I hear one of the producers go, ‘Oh Jesus, oh Christ, will somebody go and get Terry?' And we look out and this fucking dude, Terry Malick, has a conductor — he has a camera, which is a fucking conductor, basically — on his shoulder and he's out, the grass is blowing, and he's out there in a middle of a fucking lightning storm. It was beautiful. [In 2008, the success of Hollywood blockbuster Kung Fu Panda shocked China's ruling Communist party. It sparked soul-searching among Chinese political elites and film producers.] They asked themselves: how could a quintessential Chinese film achieve such a success with American Hollywood? I think movies have a responsibility to reflect something real about the concerns people face in their lives. If you can make that compelling, it's going to be worthwhile to me. But I also like movies that are timeless, that exist outside social commentary. [Such as?] My wife's movie [The Lost Daughter ]. I was on a talkshow and they said: ‘Can you explain what's happening before we show the clip?' I was like: ‘Nuh-uh. I don't think I can.' That's the sort of movie I love. One that you can't set up. Am I working for the Goliath that's killing the David? Unless you have a Marvel star, financing any film is very, very, very, very difficult—no matter how important the story, no matter how urgent the story, no matter how talented and awarded and appreciated the artist is. Actors are prostitutes because they're asked to play other feelings. This prostitution is not profane; it's a sacred act that we give them...

I've said many times that if actors are paid much more than the director or the screenwriter, for working on a film for perhaps only a tenth the amount of time, it's because they have to give the work their own flesh and their own emotions… which is not necessarily without psychological consequences. The universal truth that I refuse to believe has died is that a really good film is going to work.

The specifics of what that means is always in flux. A film this good has an audience and there's no fighting that.

My instinct is that this movie [

“Drive My Car” ] wouldn't have made as much noise if it went to streaming after three weeks. Before, you had to choose the platform; now you have to choose the content. If you position a three-hour foreign language film as content, it's going to lose out a lot of the time. I hate messages. But if there is a message in BigBug , it is that artificial intelligence will never kill human beings because they will stay stupid. They don't have a soul. They try to have a sense of humour, but they don't understand anything. [Laughs] I do believe it is a discussion that has to be had, it's utterly legitimate. You know, if someone who's not Jewish can't play Jewish, does someone who's Jewish play someone who's not Jewish? There's a lot of terrible unfairness in my profession. “Jackass” wouldn't be so popular if it didn't represent a profound desire to laugh at other people's pain, to find catharsis in the very thing that scares us all — the universal fragility of the human body. (Finished in the midst of the pandemic, “Jackass Forever” embodies this spirit even more than its predecessors.) At its center,

Johnny

Knoxville comes across as an experimental performance artist. Even if he's disinterested in the complex sociological impulses at the core of his work, he's been forced to contemplate them as a result of his success. If I had to bet, a drama like Argo would not be made theatrically now. That wasn't that long ago. It would be a limited series. I think movies in theaters are going to become more expensive, event-ized. They're mostly going to be for younger people, and mostly about 'Hey, I'm so into the Marvel Universe, I can't wait to see what happens next.' And there'll be 40 movies a year theatrically, probably, all IP, sequel, animated. The Last Duel really clinched it for me. I've had bad movies that didn't work and I didn't blink. I know why people didn't go—because they weren't good. But I liked what we did. I like what we had to say. I'm really proud of it. So I was really confused. And then to see that it did well on streaming, I thought, 'Well, there you go. That's where the audience is. [The Chinese streaming site, Tencent Video, removed the entire explosion scene at the end of Fight Club with captions: “Through a clue provided by Tyler, the police rapidly figured out the whole plan and arrested all criminals, successfully preventing the bomb from exploding."] In my other works, we have kind of a mystery, kind of a puzzle, and that puzzle creates suspense. In this one, instead of a puzzle, we have ambiguity. There is no mystery anywhere in this story, but the whole atmosphere is full of ambiguity. The bulk of the energy I spent on this screenplay was to replace mystery with ambiguity but still give the feeling of suspense. My wish is that one day I will make a film where people will go into theaters and completely forget it's a film. They will feel, ‘This is a life.' Perfection in the cinema consists in the knowledge that whatever happens there is a barrier between the film and ‘reality'. Colour has removed this last barrier. If there is nothing false in a film it is not a film – one is in competition with the documentary and the result is very boring. Like much of the film shot for American television, which I find lacking in any fictional dimension, anti-dramatic, over-documentary and very boring. And a large part of modern cinema is like that.

|

||

Note: My favourite series of 2021

|

||

For me, the film that marks the beginning of the period of decadence in the cinema is the first James Bond – Dr. No [1962]. Until then the role of the cinema had been by and large to tell a story in the hope that the audience would believe it. There had been a few minority films which were parodies of this narrative tradition, but in the main a film told a story and the audience wanted to believe that story. And at this point we might reopen the old polemic about Hitchcock. For years English critics were reluctant to accept that the films Hitchcock made in America were superior to those he had made in England. The difference for me lies in the fact that Hitchcock's desire to make the audience believe the story is stronger in his American films than in his English ones. It was my aunt Talia Shire who first said to me, ‘Naturalism is a style,' And I was also a big believer in arts synchronicity, and that what you could do with one art form you could do and another meaning. You know, in painting, for example, you can get abstract, you can get photorealistic, you can get impressionistic, why not try that with film performance? I was experimenting with what I would like to call Western Kabuki or more Baroque or operatic style of film performance. Break free from the naturalism, so to speak, and express a larger way of performance. In the mainstream cinema of the 80s in Hollywood, filmmakers like John Landis, Jonathan Demme and Joe Dante were working within the boundaries of this Hollywood system but they were really making very radical films. A movie like Trading Places [1983] is such a wonderful, beautiful homage to Preston Sturges's cinema, and at the same time it's such an incredible and beautiful parable of what capitalism is, and how we can fight it. When you see a comedy of manners today, made within the system of studios or streamers, it's completely toothless and very disappointing. Reviewing the data on this site demonstrated that people do tend to like villains who share their traits, people became fans of villains who were similar to them at higher rates than they became fans of heroes who were like them. There is a lot of pressure on filmmakers, from the media, to get them to introduce a political dimension, even an artificial one, into their work. It is very important to resist this. Filmmaking should be a pleasure, not a duty. You don't make a film to please a particular section of public opinion. You make a film for your own pleasure and in the hope that the audience will share it. If filmmaking became a duty I would do something else.

|

||

Note: These are my favourite films representing 20th century Russia/Soviet/Russia.

|

||

How is [the movie business] changing?

One of the fundamental ways it's changing is that the people who want to see complicated, adult, non-IP dramas are the same people who are saying to themselves, ‘You know what? I don't need to go out to a movie theater because I'd like to pause it, go to the bathroom, finish it tomorrow.' It's that, along with the fact that you can watch with good quality at home. It's not like when I was a kid and the TV at home was an 11-inch black-and-white TV. I mean, you can get a 65-inch TV at Walmart for $130. There's good quality out there and people are at home streaming in Dolby Vision and Dolby Atmos. It's all changed. I'm an actor, and that's what I do for a living: try to be people that I'm not. What do we do with Marlon Brando playing Vito Corleone? What do we do with Margaret Thatcher played by Meryl Streep? Daniel Day-Lewis playing Lincoln? Why does this conversation happen with people with accents? You have your accent. That's where you belong. That's tricky. Where is that conversation with English-speaking people doing things like ‘The Last Duel,' where they were supposed to be French people in the Middle Ages? That's fine. But me, with my Spanish accent, being Cuban? What I mean is, if we want to open the can of worms, let's open it for everyone. The role came to me, and one thing that I know for sure is that I'm going to give everything that I have. I wouldn't say no [to TV serie], but I wouldn't know where to begin. I had this conversation with Quentin [Tarantino]: I think neither one of us has a problem with writing material. Sometimes the problem can be cutting material, you know? Sometimes you're in the middle of writing something and you have way more than you need and you go, Well, maybe this should be a TV show, you know? That's not the solution. The solution is not to just use a lot of B-material and make a longer-form thing. The solution would be cut down, get to your good material, tell your story properly and make a film. So, I've never thought about it in a very serious way. I don't watch a lot of it, so I don't know exactly how it works. The structure is something I'd have to learn, you know. I don't mean to sound like an idiot. Of course I've seen episodic television, but there's a rhythm to that writing and a structuring of how you pull a story over multiple episodes, which at this point would be a huge learning curve. The people who do it, do it incredibly well. I think I'd feel a little bit like a tourist trying to step into that. There is a danger that we [documentary filmmakers] are so hooked on story. Particularly the kind of Western, three-act story structure with conflict and resolution, and a hero — often a him — who wants something he can't have: How's he going to get it? That's what many gatekeepers mean by story … the beautiful diversity and richness of the non-fiction form is being narrowed and all commodified into that kind of story. Non-fiction is wearing the clothes of fiction or television and attracting those audiences because it's so satisfying. One of the things I've wrestled with is trust, and Sidney [in "Scream" ] trusted no one. Did she really know her mother? Is her boyfriend who he says he is? In the end she wasn't even trusting herself. As a gay kid, I related to the final girl [the surviving woman at the end of a horror movie], and to her struggle because it's what one has to do to survive as a young gay kid, too. You're watching this girl survive the night and survive the trauma she's enduring. Subconsciously, I think the Scream movies are coded in gay survival. I think what it boils down to — what we've got today [are] the audiences who were brought up on these fucking cell phones. The millennian, [who] do not ever want to be taught anything unless you told it on the cell phone…This is a broad stroke, but I think we're dealing with it right now with Facebook. This is a misdirection that has happened where it's given the wrong kind of confidence to this latest generation, I think. The Hand of God is a completely different movie for me. I was scared to do these kind of scenes that I never did before. I normally adopt a certain style: I move my camera around because I'm searching for the truth. In this case, the approach was completely the opposite. Because I already had the truth, I didn't need to go and look for it. I decided that if I kept my camera still, [the actors] would feel freer to express themselves with sincerity and authenticity, which is what they did. It represents a divine opportunity to really sink into something that comes very naturally to me … which is to be really slow, which I naturally am, and to be really still, which I naturally am — I'm a lazy beast, I like to be slow when I'm not in a social situation where I get drawn into the energy of other people, because I'm also porous. By being dislocated, she is super connected, which makes her still because she's not actually driving anything. She's not offering anything. She's not chattering away. She's not making any kind of social pose, she's sort of borderless. I worked harder

[in The Amazing Spider-Man 2 ]

than I've ever worked on anything and I'm really proud of it. But I didn't feel represented. There was an interview I gave where I said, ‘Why can't Peter explore his bisexuality in his next film? Why can't [his girlfriend] MJ be a guy?' I was then put under a lot of pressure to retract that and apologize for saying something that is a legitimate thing to think and feel. So I said, ‘OK, so you want me to make sure that we get the bigots and the homophobes to buy their tickets?' I don't want to use the casting consultant as cover. I want to tell you my opinion on this [casting in

“Being the Ricardos” ] and I stand by it, which is this: Spanish and Cuban aren't actable, okay? They're not actable. By the way, neither are straight and gay. Because I know there's a small movement underway that only gay actors should play gay characters. Gay and straight aren't actable. You could act being attracted to someone, but most nouns aren't actable. I loved the fact that you can explore complex and controversial work and the audience in their homes are totally up for it, whereas with film it's hard to do work like that, because as soon as some exec says they don't understand it, you've lost the game. But, to be honest, I was so exhausted after [TV series] Top of the Lake that I thought, ‘Oh my God, making a two-hour film seems like heaven.' When the most intense moment of a James Bond film exploits the potential death of a child — [...] — it's time to give up. No Time to Die (series sequel 24) proves that the decades-old James Bond franchise has reached a dead end. The turn toward sadism that began with Daniel Craig's angry, sinister interpretation of 007 has reached an unconscionable level of heartlessness. Does anyone believe in the series anymore? Even the producers have forsaken the ethical delight that once guaranteed a Bond movie's insouciance and thrills. I mean, of course, I have an artistic envy of those people, how plugged into a moment a musician can be, how different their medium is to mine. But none of my films have been driven by that. They're more about what the music means culturally, how it changed the world. I remember saying to people during the Dylan project: ‘I would want to make a film about Bob Dylan even if I didn't care for his music,' simply because of his impact and uniqueness and complexities and contradictions and the way he gets to some core idea about America and then reflects that back in the various chapters of his life. It was at the L.A. premiere of ‘Children of Dune,' and

[Claudia Black]

said to me, that the thing with this shit, i.e. science fiction, is that you have to believe it more than you believe good writing. Good writing, you can just do. It's easier. But this stuff is hard, because it's so bonkers, you know what I mean? I've really, I've always remembered that advice and taken it to heart. When I first got into the movie business — it's been almost 40 years ago — the reason I was able to make movies with Ethan [Coen], the reason we were able to have a career is because the studios at that point had an ancillary market that was a backstop for more risky films, which were VHS cassettes or all these home video markets, which is essentially television. It can be seen as an event in history that lasted for however long it lasted, this cancel culture, this instant rush to judgement based on what essentially amounts to polluted air. It's so far out of hand now that I can promise you that no one is safe. Not one of you. No one out that door. No one is safe. ‘True Detective' was presented to me in the way we pitched it around town — as an independent film made into television. The writer and director are a team. Over the course of the project, Nic [Pizzolatto, writer] kept positioning himself as if he was my boss and I was like, ‘But you're not my boss. We're partners. We collaborate.' By the time they got to postproduction, people like [former HBO programming president] Michael Lombardo were giving Nic more power. It was disheartening because it didn't feel like the partnership was fair. I just wrote a little something, for writers, really. Write the tale that scares you, that makes you feel uncertain, that isn't comfortable. I dare you. In a world that entices us to browse through the lives of others to help us better determine how we feel about ourselves, and to in turn feel the need to be constantly visible, for visibility these days seems to somehow equate to success—do not be afraid to disappear. From it. From us. For a while. And see what comes to you in the silence. I dedicate this story to every single survivor of sexual assault. Thank you. Black Panther's relatively novel concept imagined the faux African kingdom Wakanda, whereas Shang-Chi pilfers from already familiar and much more original and artistic Chinese martial-arts genre movies — reducing them to the level of Marvel junk. The memory as a kid was always, we were waiting for what happened in America. So, you know, films were always shown in America first. I remember hearing about Indiana Jones or the next Star Wars, and you'd see pictures on the news of people queuing for the cinema in the States and you'd think: ‘Well, when are we gonna get it?' There was always this sense of it being ahead. They did a phenomenal job of selling us this lifestyle that just seemed so other and glamorous and cool. In “Emily in Paris” and other recent programming, Netflix is pioneering a genre that I've come to think of as ambient television. It's “as ignorable as it is interesting,” as the musician Brian Eno wrote, when he coined the term “ambient music” in the liner notes to his 1978 album “Ambient 1: Music for Airports,” a wash of slow melodic synth compositions. Ambient denotes something that you don't have to pay attention to in order to enjoy but which is still seductive enough to be compelling if you choose to do so momentarily. Like gentle New Age soundscapes, “Emily in Paris” is soothing, slow, and relatively monotonous, the dramatic moments too predetermined to really be dramatic. Nothing bad ever happens to our heroine for long. The earlier era of prestige TV was predicated on shows with meta-narratives to be puzzled out, and which merited deep analyses read the day after watching. Here, there is nothing to figure out; as prestige passes its peak, we're moving into the ambient era, which succumbs to, rather than competes with, your phone.

|

||

|

||